venerdì 5 dicembre 2014

New Mafia Discovered in Rome - "Mafia Capitale", 37 people arrested

Etichette:

arrest,

capitale,

carabinieri,

cosa nostra,

discovered,

fascism,

in,

italy,

mafia,

new,

roman mafia,

rome,

ros,

terrorism,

video

mercoledì 3 dicembre 2014

Mafia a Roma, 37 arresti per appalti del comune - articolo La Repubblica

Maxi operazione a Roma per "associazione di stampo mafioso" con 37 arresti,

di cui 8 ai domiciliari, e sequestri di beni per 200 milioni. Un

"ramificato sistema corruttivo" in vista dell'assegnazione di appalti e

finanziamenti pubblici dal Comune di Roma e dalle aziende

municipalizzate con interessi, in particolare, anche nella gestione dei

rifiuti, dei centri di accoglienza per gli stranieri e campi nomadi e

nella manutenzione del verde pubblico: è quanto emerso dalle indagini

del Ros che hanno portato alle misure restrittive e ai sequestri da

parte del Gico della Finanza. Le accuse vanno dall'associazione di tipo

mafioso, estorsione, usura, corruzione, turbativa d'asta, false

fatturazioni, trasferimento fraudolento di valori, riciclaggio e altri

reati. "Con questa operazione abbiamo risposto alla domanda se la mafia è

a Roma - ha spiegato il procuratore capo di Roma, Giuseppe Pignatone,

nel corso della conferenza stampa dopo la maxi-operazione - Nella

capitale non c'è un'unica organizzazione mafiosa a controllare la città

ma ce ne sono diverse. Oggi abbiamo individuato quella che abbiamo

chiamato 'Mafia Capitale', romana e originale, senza legami con altre

organizzazioni meridionali, di cui però usa il metodo mafioso". Nello

specifico, ha riferito Pignatone, "alcuni uomini vicini all'ex sindaco

Alemanno sono componenti a pieno titolo dell'organizzazione mafiosa e

protagonisti di episodi di corruzione. Con la nuova amministrazione il

rapporto è cambiato ma Massimo Carminati e Salvatore Buzzi (presidente della cooperativa 29 giugno arrestato oggi) erano tranquilli chiunque vincesse le elezioni".

Gli arresti. A capo dell'organizzazione mafiosa l'ex terrorista dei Nar, Massimo Carminati che, secondo gli investigatori, ''impartiva le direttive agli altri partecipi, forniva loro schede dedicate per comunicazioni riservate e manteneva i rapporti con gli esponenti delle altre organizzazioni criminali, con pezzi della politica e del mondo istituzionale, finanziario e con appartenenti alle forze dell'ordine e ai servizi segreti''. L'organizzazione di Carminati è trasversale. Ne è convinto il procuratore capo di Roma Giuseppe Pignatone che sull'argomento ha precisato: "Con la nuova consiliatura qualcosa è cambiato, in una conversazione Buzzi e Carminati prima delle elezioni dicevano di essere tranquilli". Carminati diceva a Buzzi, ha spiegato Pignatone: "Noi dobbiamo vendere il prodotto, amico mio, bisogna vendersi come le puttane" e di fronte alle difficoltà presentate da Buzzi, Carminati aggiungeva: "Allora mettiti la minigonna e vai a battere con questi".

fonte: http://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2014/12/02/news/perquisizioni_alla_pisana_e_in_campidoglio-101923254/

Gli arresti. A capo dell'organizzazione mafiosa l'ex terrorista dei Nar, Massimo Carminati che, secondo gli investigatori, ''impartiva le direttive agli altri partecipi, forniva loro schede dedicate per comunicazioni riservate e manteneva i rapporti con gli esponenti delle altre organizzazioni criminali, con pezzi della politica e del mondo istituzionale, finanziario e con appartenenti alle forze dell'ordine e ai servizi segreti''. L'organizzazione di Carminati è trasversale. Ne è convinto il procuratore capo di Roma Giuseppe Pignatone che sull'argomento ha precisato: "Con la nuova consiliatura qualcosa è cambiato, in una conversazione Buzzi e Carminati prima delle elezioni dicevano di essere tranquilli". Carminati diceva a Buzzi, ha spiegato Pignatone: "Noi dobbiamo vendere il prodotto, amico mio, bisogna vendersi come le puttane" e di fronte alle difficoltà presentate da Buzzi, Carminati aggiungeva: "Allora mettiti la minigonna e vai a battere con questi".

fonte: http://roma.repubblica.it/cronaca/2014/12/02/news/perquisizioni_alla_pisana_e_in_campidoglio-101923254/

giovedì 14 agosto 2014

A Critical Analysis of Anti-Corruption Agencies [ESSAY]

A

critical analysis of anti-corruption agencies

Author: Alessandro D'Alessio

Anti-corruption

agencies (ACAs) are public funded bodies that have the specific duty to tackle

corruption through both repressive and preventive activities and, in general,

are built under acts of an executive or legislature decree[1].

Etichette:

2014,

ACAs,

agencies,

alessandro,

analysis,

anti-corruption,

critical,

d'alessio,

essay,

Sussex,

University

sabato 19 luglio 2014

mercoledì 16 luglio 2014

martedì 15 luglio 2014

mercoledì 28 maggio 2014

Camorra mafia 'super boss' Antonio Iovine turns state witness [The Guardian/UK]

One of four bosses of Casalesi clan within Camorra mafia is collaborating with investigators in Naples, Italian media says

A so-called super boss of a powerful clan within the Camorra mafia has turned state witness and is collaborating with investigators in Naples, Italian media reported on Thursday.

Antonio Iovine, one of the four bosses of the infamous Casalesi clan, started answering the questions of anti-mafia prosecutors earlier this month, La Repubblica wrote. The Naples daily Il Mattino declared it "a historic choice".

Aged 49, but known to all as o'ninno (the baby) for his youthful face and his rapid ascent of the Casalesi power structure, Iovine is thought to have effectively led the business side of the clan's activities before his arrest in 2010 and subsequent jailing for life.

All four bosses are behind bars after a big trial that concluded in 2008. But "until now, none of the core leadership of the Casalesi has ever turned state witness", said John Dickie, professor of Italian studies at University College London and the author of several books on the mafia. "It will be interesting to see if this is the start of the fissuring of this leadership group."

Reports of Iovine's decision were greeted with excitement by Roberto Saviano, a journalist whose bestselling book Gomorrah earned him repeated death threats from the Casalesi, a group known to have made huge inroads into construction, waste disposal and politics.

"This is news that risks changing for good what we know to be true about business and organised crime not only in Campania [and] not only in Italy," he wrote.

"He [Iovine] is someone who knows everything. And so now everything could change. The earth is trembling for a large part of the business and political worlds – and for entire branches of institutions.

"The companies, big and small, which … were born and prospered thanks to the flow of cash from Antonio Iovine, feel as if they're in a room whose walls are increasingly closing in."

Saviano, who lives under police protection, grew up in Casal di Principe – the fiefdom of the Casalesi – and took particular aim at the clan's activities in his book, which went on to become an award-winning film directed by Matteo Garrone.

He said that, while the phenomenon of mafia bosses turning police informers was nothing new, Iovine's move was a first for the Casalesi top brass. The only comparable pentito, he said, had hailed from a previous generation.

"Iovine is the organisation," said Saviano, predicting that his decision to talk could yield information not only about business and the criminal underworld, but also about the past two decades of politics in Italy – not least Nicola Cosentino, a key ally of the former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi in the Campania region around Naples.

Cosentino was arrested in April on suspicion of colluding with the mafia to favour his family business, allegations his lawyer has described as absurd.

Iovine was sentenced to life, in absentia, at the end of the so-called Spartacus maxi-trial in 2008, and to 21 years and six months at the end of a trial this year. So far, none of the other Casalesi bosses in prison – Francesco Schiavone (AKA Sandokan), Francesco Bidognetti or Michele Zagaria – have collaborated with investigators.

Dickie said the development could prove interesting "more for what he [Iovine] can reveal about the past", particularly regarding politics. However, testimony from mafiosi turned state witnesses was always handled with great caution and its use was "controversial, not least because of [the pentito's] motives".

The interior minister, Angelino Alfano – Berlusconi's former would-be successor – appeared to reflect this ambiguity, telling Sky TG24 television on Thursday: "Sincere repentances have helped the fight against the Cosa Nostra and the [Calabrian] 'Ndrangheta … If the same thing happens with the Camorra it could open interesting scenarios and could even lead us to its defeat."

Luigi De Magistris, the former anti-mafia prosecutor who is now mayor of Naples, was quoted as saying the news was a positive development, opening breaches within the Camorra clans, and a sign of "collaboration with justice".

SOURCE: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/22/camorra-mafia-boss-antonio-iovine-state-witness-italy-naples

Article by Lizzy Davies

venerdì 23 maggio 2014

venerdì 2 maggio 2014

Tangentopoli/Bribesville [Essay]

Tangentopoli

The Tangentopoli

(Bribesville) case was probably the greatest corruption scandal happened in

Italy. It caused the collapse of an entire party system that had characterised

the First Republic[1]

since 1946. About five hundred members of Parliament, six former Prime Ministers

and thousand local administrators were investigated within the judicial inquiry

called Mani Pulite (Clean Hands) led

by Antonio Di Pietro. Everything began in February 1992 when a socialist

manager and director of a nursing home in Milan, Mario Chiesa, was arrested,

accused of a small bribe (7 million Lire, about 5000 GBP as of 2013) from a

businessman who had a cleaning contract at the home. At first Bettino Craxi, at

the time leader of the Socialist Party (PSI), affirmed that it was an isolated

case. However Chiesa, questioned by the Mani

Pulite pool of prosecutors, explained how the bribe was, by then, a sort of

“tax” and revealed a more complex network of bribery that involved almost all

political parties, especially the PSI and the Christian Democratic Party (DC).

Etichette:

alessandro,

bettino,

bribesville,

case,

chiesa,

corruption,

craxi,

crime,

d'alessio,

di pietro,

essay,

italy,

mani,

milano,

pool,

prima,

pulite,

repubblica,

scandal,

tangentopoli

venerdì 21 marzo 2014

-The CBA- [Article]

Anti-Corruption Efforts in

Poland

-The CBA-

Review by Alessandro D’Alessio

The Central Anti-Corruption Bureau

(CBA) is a polish special service that has the specific objective to combat

corruption in public and economic life, especially in local and public government

institutions as well as fighting against actions that can have a negative

impact to the State’s economic interest. The Act of 9 June 2006 on the Central

Anti-Corruption Bureau regulates its activities. The Head of the CBA, appointed

for a term of 4 years, is the central authority of the government

administration; the Prime Minister appoints him after a consultation with the

President of the Republic of Poland, the Special Services Committee and the

Parliamentary Committee for Special Services; the Head of the CBA may be

reappointed only once.

domenica 2 marzo 2014

martedì 25 febbraio 2014

"Corruption and Organized Crime in Europe: Illegal partnerships" [Book Review]

Gounev, Philip;

Ruggiero, Vincenzo et al.

Corruption and Organized Crime in Europe: Illegal partnerships

Taylor and Francis 2012

Corruption and Organized Crime in Europe: Illegal partnerships

Taylor and Francis 2012

Review by Alessandro D’Alessio

With

“Corruption and Organized Crime in Europe” the authors aim to define the

relationships between corruption and criminal organizations within the 27

Member States of the European Union. Ruggiero and Gounev, through theoretical

arguments and empirical data analysis, describe and succeed in outlining

different aspects of these phenomena with a deep analysis that concerns many

different fields.

The book is split in two

distinct parts. The first one deals with definitional problems related to the

notions of organized crime and corruption that often differ from one place to

another due to cultural or political background diversities as well as with

different countries legislations. Ruggiero analyses also various variables

suggesting that the quantitative aspects, the number of the individuals

involved in a criminal group, the notion of “continuing basis” and

“professionalism” help to define what criminal organizations really are.

Throughout the book they consider organized crime as “crime in organization”

highlighting the importance of the legal-illegal nexus. This latter refers to

when organized groups gain access to the official economy and to the world of

institutional politics. Through the notion of criminal networks the authors

help the reader understand the relationship between corruption and organized

crime because the entry into licit business has to be favoured by a web of

contacts with politicians and members of the economic sector. They provide also

a wide range of observations to what concerns the relationships between

corruption and democracy leading to the idea that corruption exacerbates the

moral and political de-skilling of the electorate.

Then the inquiry moves to a

deeper description that involves public bodies, the private sector and criminal

markets.

As for the public bodies

the writers show how corruption is used as a tool of influence and also a way

to communicate with countries’ administrations as well as the judiciary

systems, the police and the politicians. However the data offered by the EU and

other organizations, such as Transparency International, display several

difficulties in the measurement of the issue. Introducing the concept of

“white-collar” offences they underline how, especially in certain areas such as

Italy or Southern France, local criminal elites have always been colluded with

local politics. Ruggiero and Gounev outline that corrupt relationships can be

sporadic or symbiotic. This latter type can be found in specific towns where

parallel power structures are developed and democratic principles are simply

subverted leading to the phenomenon of “state-capture”.

In the following chapter

Gounev describes the scope of private sector corruption for criminal organizations

that is to penetrate and take advantage of a private company against the will

of its owner. He explains that criminals do this mainly because they want to

facilitate criminal activities or launder profits from other crimes. He

suggests also some anti-corruption measures for companies such as following the

international standards contained in the United Nations Convention against

Corruption, internal whistleblowing and anti-bribery policies even though criminal

behaviours are, in the majority of companies, detected by outside bodies

(police investigations).

With regard to criminal

markets the authors aim to demonstrate how corruption facilitates particular

“organized criminal activities” such as the illegal cigarettes market,

prostitution and trafficking in human beings for sexual exploitation, illicit

drugs market, vehicle theft and extortion racketeering. They give wide

information concerning different aspects of corruption (administrative, police,

judicial, private sector corruption etc.) to each of the illegal activities

studied.

The second part of the book

analyses in depth some European countries and how rooted the two phenomena are.

The countries are Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy, Russia, Spain and UK.

Tihomir Bezlov and Gounev describe the Bulgarian situation affirming that the

scale of corruption that has permeated public and private sectors in the

country since the early 1990s is vast. The four main institutions (political,

judicial, police and custom) seem still to be seriously corrupt. The chapter

begins with an overview of Bulgaria recent history that helps the reader in learning

the current state of the institutions. The same formula has been adopted in the

chapter regarding Russia because it’s useful to study the transition period to

market economy in order to understand the social and economic changes that

these countries are still facing. In Eastern Europe white-collar offenders are

not considered as something separate from organized crime while the economic

transition and privatisation processes have strongly enforced criminal

activities and the creation of new criminal organizations. In the case of Russia it’s interesting the

historical overview that tends to underline that cultural behaviours, like the

patron-client relationship, of the 18th Century Tsarist Russia have

been firstly embedded in the Soviet Russia after the 1917 October Revolution

and then maintained after the fall of Communism in 1989. This chapter, written

by Paddy Rawlinson, illustrates that the URSS was characterized by a widespread

corruption as an intrinsic component of the system itself. Nowadays a lack of

political will in the fight against corruption is observable despite Putin’s

and Medvedev’s reforms announcements.

While France and UK are

described as countries characterized by low levels of corruption Spain, Greece

and Italy are facing serious problems in this sense. Spain, whose chapter is

written by Alejandra Gòmez-Céspedes, is defined as a criminal hub with severe

drugs and illegal immigrations problems. With the help of charts, provided by

the Ministry of the Interior every year, the reader can be fully aware of the

huge amount of drugs that pass through this country to reach the whole Europe.

Greece has got similar problems and has to deal also with immigrant and

indigenous organized crime. On the one hand there are the Albanians, Russians,

Romanians, Turkish, Iraqi and Bulgarians. Every group is specialized in a

particular criminal activity like drug trafficking, counterfeiting or cigarette

smuggling. On the other hand Greek organized criminal groups often provide

means of transportation for cocaine across the Atlantic route along with other

criminal actions (extortions, human trafficking). Regarding Italy, Ruggiero describes

the main criminal organizations (‘Ndrangheta, Camorra, Cosa Nostra and Sacra

Corona Unita) very accurately and depicting them as organizations that

constitute “power systems” because of their continuous contacts with the

“official world” of politics. He narrates the story of these groups beginning

from the unification of the Italian peninsula, a fundamental approach to figure

out such a complex phenomenon. Citing the State Audit Board (the Corte dei

Conti), Ruggiero explains that corruption is widespread throughout the country

and shows that there is a “mafia method” in conducting business and doing

politics. Moreover the infiltration of mafia organizations is very strong

across the regions of Southern Italy, especially in Calabria where the

‘Ndrangheta has enjoyed little attention by institutions and public opinion. In

the end Ruggiero underlines the importance of the violence factor; he outlines

that the elite in Italy has never renounced violence and has never really

managed to make the transition to a modern social order based on legality.

In

conclusion I find this book very well written, accurate and supported by strong

empirical evidence. The general-to-specific pattern turns out to be very useful

to the reader and the countries chosen are helpful in defining the specific

aspects of corruption, the organized crime and the related features. My only

criticism is that the cultural and structural differences between mafia and

“common” organized crime are not examined in depth as well as the economic

power that such criminal groups exert on the European capitalistic system.

Apart from that, I feel to suggest this book to everyone is interested in these

issues and wants to know more about the world he lives in.

Etichette:

and,

book,

corruption,

corruzione,

crime,

europe,

illegal,

in,

libro,

mafia,

organized,

partnerships,

recensione,

review

mercoledì 19 febbraio 2014

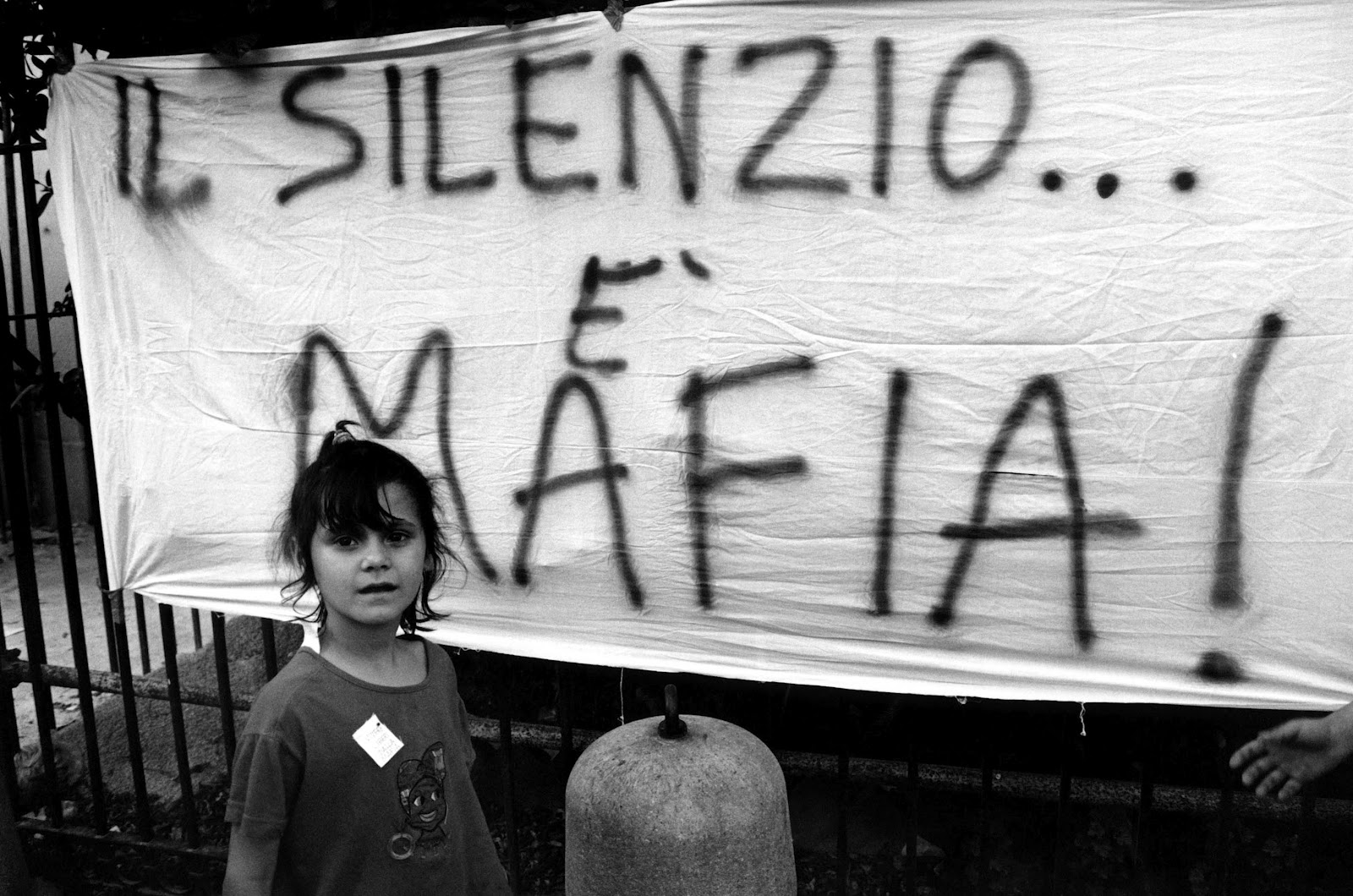

The Mafia System in Italy [Essay]

[Silence... is Mafia!]

The

Mafia System in Italy

Essay by Alessandro D'Alessio

Mafia

represents a cultural, economical and political Italian phenomenon. Mafia

organisations are criminal groups whose main objective is to make business, sharing

a common background of values and culture. Its complexity requires a deep

analysis in order to understand the reasons that allow it to be such a key

player in the Italian history. Their power could be explained by social

consensus given by a certain culture in specific poor areas, especially in the

south, but, as prosecutor of Palermo Roberto Scarpinato affirmed[1],

mafia issues would have been erased many years ago if politicians hadn’t always

been so prone to it. The link between the political world and the criminal and

violent universe of the Italian mafia existed even before the unification

process of 1861[2].

After the end of World War II its presence has become more accentuated gaining an

unofficial but constant representation throughout Italian institutions. These

two powers, mafia and the institutions, are able to contact each other using

corruption as means of communication, establishing and maintaining a specific

order: the “Mafia System”.

In

Italy we can distinguish five different mafia organisations: Cosa Nostra and Stidda in Sicily, ‘Ndrangheta

in Calabria, Sacra Corona Unita in

Puglia, Camorra in Campania and in

the city of Naples[3].

It’s useful to make a brief overview of the most economically powerful[4]

in their features and differences. The Sicilian Mafia, called Cosa Nostra, probably born at the

beginning of the XIX Century[5],

has been defined as a terrorist-mafia association by the “pentito” Gaspare Spatuzza in 2009. He explained the adjective “terrorist”

referring to the mafia attacks in Florence and Milan that, in 1993, killed ten

innocent people[6].

‘Ndrangheta[7],

whose name comes from the Greek “andragathos”[8],

is not well-known to the national public even if its influence on the Italian

political life goes back to the 1869, when Reggio Calabria administrative

elections were cancelled because of gerrymandering. In those years a criminal

organisation, initially defined “picciotteria”,

began to spread its power in Reggio Calabria and Catanzaro areas and had

characteristics that were similar to the Camorra’s,

which, in turn, had been inspired by the Spanish “Garduna”, a Toledo secret association created in 1417[9].

Nowadays ‘Ndrangheta is one of the

most powerful criminal organisations of the planet and it owns almost the

monopoly of the cocaine smuggling in Europe[10].

In 2008 ‘Ndrangheta was included in

the drug trade black list by the USA government[11].

The Camorra is a mafia phenomenon

that involves the masses and it’s the only one with urban origins[12].

Camorristi[13]

call their organisation “O’ Sistema”[14].

The lack of long-lasting hierarchical structures and rules makes the

organisation very flexible and dynamic. Camorra,

like other mafia organisations, has had strong contacts with the political

system since the 1865 general elections. “O’

Sistema”, differently from Cosa

Nostra, doesn’t propose an alternative order in opposition to the State but

rules social disorder[15].

A

common characteristic that links all organisations is the fact that the most

important members have particular nicknames. Francesco Schiavone, former head

of the Casalesi[16],

has been dubbed “Sandokan”[17];

Michele Greco, Cosa Nostra boss of

the 1980s, was dubbed “Il Papa”[18]

[19];

Giuseppe Morabito, boss of the Morabito clan, is called “U’ Tiradrittu”[20] [21].

Nicknames are used by organisations as a fundamental communication strategy to

be easily and quickly recognizible.

In

order to understand the relationships between politics and mafia is appropriate

to define values and structures of such organisations. The mafiosi[22] think that laws

are for cowards but rules are for “men”. These “rules of honour” don’t tell

them to be honest, on the contrary they tell them how to command. They think it’s

only a luxury for the rich believing in the dream of a “better world”. Values

like freedom, justice or equality are for the weak; they assume that if they

risk all, they have all. They also know they will be killed or betrayed by someone

very close to them like a friend, and so even friendship is considered

insignificant. There’s no way to think it’s possible to live without hiding,

running away or going to jail; if you do that, you’re not a real “man”. Organisations

know that human beings are depraved and corrupt, so new members have to know

the differences between a common man and a mafioso.

The latter knows exactly what and when problems will happen while the former is

cheated by bad luck or fate. They also show no compassion for betrayers who are

inevitably death sentenced; there’s no forgiveness, the betrayer will always be

on their list and if he runs away his family or allies will be killed[23].

It’s also true that it doesn’t exist a natural way of being a mafioso from an

anthropological perspective, they have only few occasions to communicate their

power publicly so they study methods to act like “mafiosi” for example dressing like Michael Corleone or using

specific accents while speaking. They artificially create a “mafia style” that

must be easy to recognize and to understand. They get their inspiration from

the movies, not the opposite. Typical examples are the arrest of Cosimo Di

Lauro, a Camorrista, when he showed himself

to the media dressed like “The Crow”[24]

and Walter Schiavone’s mansion in Casal di Principe that looked like the Tony

Montana’s “Scarface” one[25].

Such cynical

and ferocious mafia “ethics” seem to fit perfectly with democracy and its

institutions. Especially in the last few years, politicians are those who

activate themselves to create contacts with the organisations[26].

Politicians ask them to vote for their party since mafia controls large

portions of the economy and of the population on the Italian territory. This is

very common at all levels, administrative, general and even the primaries of

the Democratic Party[27].

But why have politicians proven particularly prone to mafia groups gaining

prominence in public life? First of all mafia is a cultural problem. Vast areas

in southern regions of Italy are quite poor and completely left alone by the

State; thousand of people recognise criminal organisations as the official

authority. Frequently mafia is able to provide jobs and protection. Those regions

are generally peaceful places even though such tranquillity is obtained through

fear and threats. In a country where rights are not fully respected, mafia

gives people a chance to live and, in this perspective, the State is judged to

be an enemy. It’s a fact that a degraded ruling class degrades people and vice

versa in a vicious circle[28].

Joining

an organisation requires a specific initiation ritual. Cosa Nostra calls it “Punciuta”[29]

consisting of a little cut on the index finger of the hand that the initiate

uses to shoot. This cut is made with a bitter orange thorn, sometimes a

particular golden thorn, in front of the family boss and other “uomini d’onore”[30] [31].

‘Ndrangheta calls this ritual “Battesimo”[32]

and has almost religious connotations as the initiate has to pronounce a

specific formula while holding in his hands the burning picture of Saint Michael[33].

Organisational

structures are important because they mark some differences with other criminal

groups that cannot be defined as “mafia”. Simple organised groups usually disappear

when their members are killed or arrested while the mafia ones succeed in establishing

continuity and giving, from a generation to another, a whole set of values and

methods. The Sicilian Mafia is hierarchically composed by “soldati”[34]

or “uomini d’onore” that form a

“family”. This latter has a territorial based structure that allows it to

control a particular city area from which it takes the name. An elected chief

called “Rappresentante”[35]

rules the “family”. Then there’s the “Capo-decina”

that coordinates the activities of ten, or more, “soldiers”; the “Capi-Mandamento” represent three or

more territorially neighbouring families and form the “Cupola”[36]

or “Commissione Provinciale”, they also

elect the chief of the “Commissione”.

The advent to power of Totò Riina’s Corleonese Mafia brought the creation of a new

entity called “Interprovinciale” that

has the role to control all the Sicilian provinces[37].

On his

side, ‘Ndrangheta has even more

complicated hierarchical structures. The “Società”[38],

as the ‘Ndranghetisti[39]

use to call their organisation, is divided in “Società Minore” and “Società

Maggiore”. The first one is composed of the “Contrasto Onorato”, a person who is not yet a member of the

organisation; he becomes a “Picciotto”

after the “Baptism” ritual. Then he can become a “Camorrista”[40]

and if he kills at least one person he will gain the status of “Sgarrista” that is the highest rank of

the “Società Minore”. The transition

from the “Società Minore” to the “Società Maggiore” is very peculiar. The

member receives a golden key from the hierarchically superior assembly of the “Santisti” and he has to hold it until

the “Maggiore” of San Luca, the ‘Ndrangheta headquarter in Calabria, ratifies

the transition. The “Sgarrista” now

becomes a “Santista”, member of the “Santa”, quitting the ‘Ndrangheta to be part of a mixed

structure having specific roles. Indeed, the “Santista” can establish contacts with the Police forces and with

the public institutions of the State. The “Santa”

objectives concern mainly drug smuggling, kidnapping and other trades that can bring

profits. Then there is the “Vangelo”

whose members[41]

have the most important decision-making responsabilities of the organisation.

There are also other ranks like “Quartino”,

“Trequartino” and “Padrino” but the ‘Ndrangheta’s secrecy

concerning the highest personalities of the hierarchy prevents us from knowing

more precise informations about them[42].

According to the four volumes of the recent “Ordinanza

di fermo” concluding the long investigation of the Milan and Reggio

Calabria DDA[43],

some previously unknown ranks within the ‘Ndrangheta

are, in ascending order, “Crociata”, “Stella”, “Bartolo”, “Mamma”, “Infinito” and “Conte Ugolino” that should be the highest rank of the organisation[44].

Modern

mafia organisations act like big companies and their main goal is to make money

using every method. Drug smuggling, along with other illicit activities like

racketeering, pronstitution, money laundering and corruption, gives them a lot

of extra money that grants them to be extremely competitive on the legal market

controlling and building restaurants, hotels, discotheques, supermarkets and a

variety of different kind of enterprises that embrace almost every economic

field[45].

In 2013 ‘Ndrangheta has estimated annual

revenue of 52,6 billion euros that represent the 3,4% of the Italian GDP[46].

According to the Naples DDA in 2008

the Casalesi clan earned about 30

billion euros[47].

This economic power allows them to spread internationally causing serious

distortions to the free market[48].

The

knowledge of such informations is fundamental to understand how organised these

groups are in controlling the territory through complex structures and how their

criminal actions pursuit a specific, serious and professional economic strategy

able to influence the international market and the political life of nations[49].

The

cracks through which is possible to see the underground world of relationships

between organised crime and politics in Italy are given by facts.

The

first one is the “Portella della Ginestra Massacre” committed in Sicily on May

1, 1947. The bandit Salvatore Giuliano and his gang opened fire on a crowd of

poor peasants and workers gathered at Portella della Ginestra while celebrating

the Labour Day. The shoot out caused the death of 11 people and many wounded. The

reasons why Giuliano carried out the massacre aren’t totally clear till now even

though it’s sure that Cosa Nostra was

involved together with separatist Sicilian forces who wanted to guarantee the

preservation of certain balances of power in the new post-war institutional and

political framework. This latter is considered to be responsible of instigating

the massacre attempting to threaten peasant masses that were protesting against

landowners and who voted for the “People’s Block”, a coalition of the Italian

Communist Party (PCI) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), a few weeks

earlier[50].

The

Cold War is the historical background in which this system of relations is set.

Democrazia Cristiana (DC) won the

1948 general elections and inevitably mafia interests were directed towards

this party. At first they supported politicians like Salvo Lima, mayor of

Palermo, and his council member Vito Ciancimino both close to Amintore Fanfani

who was minister of the first De Gasperi governments. When Fanfani together

with Aldo Moro decided to collaborate with the PSI, mafia attentions shifted

towards Giulio Andreotti and his “corrente”[51],

joined also by Lima and Ciancimino. The DC accepted mafia votes mainly because

they were useful in the fight against communism in the attempt to contain the PCI

expanding influence. In the 1970s in Calabria ‘Ndrangheta syndicates decided to enter institutions directly;

clearly the DC was the most compromised party also because the PCI followed an

inflexible policy of expulsions with everyone in some way implicated with mafia.

The DC had also relationships with the Camorra

that can be explained through the specific case of the Cirillo’s kidnapping. In

1981 Ciro Cirillo, Neapolitan DC council member of the Campania region, was

kidnapped by the communist terrorist organisation the “Red Brigades”. Members

of the DC, Italian Secret Services and Raffaele Cutolo’s “Nuova Camorra Organizzata”[52]

were the key players for the negotiations with the terrorists. Cutolo, in jail

at that time, claimed many favours, profits for his enterprises and a judicial

preferential treatment. A few months later Cirillo was released after the

payment of a 1,4 billion Lire ransom[53].

It’s interesting to compare this case with another one that occured three years

earlier when the DC refused to negotiate with the terrorists, belonging to the

Red Brigades too, that kidnapped the then-president of the party Aldo Moro.

On his

side, in 2003 Giulio Andreotti[54]

was found guilty of cospiration[55]

with Cosa Nostra till 1980 but the sentence

was statute-barred. The verdict describes an “authentic, constant and friendly

availability of the accused towards the mafiosi

till spring 1980”[56].

Leonardo Messina, a “pentito”[57],

affirmed that he was told that Andreotti was “punciutu” which means he participated the official mafia ritual, the

“Punciuta”, to join the organisation[58].

Andreotti was accused also to be the instigator of the murder of the lawyer and

journalist Carmine Pecorelli. The “pentito”

Tommaso Buscetta testified that Gaetano Badalamenti, boss of the Cosa Nostra syndicate of Cinisi, told

him that the homicide was ordered by the Salvo cousins, Sicilian entrepenaurs

linked to the Sicilian Mafia, on behalf of Andreotti who was worried about

Pecorelli’s revelations that could have destroyed his career[59].

However in 2003 the Cassation Court cleared him from this accusation[60].

The “Trattativa Stato-Mafia”[61]

is one of the most recent and interesting investigations able to disclose a

network of relationships between politicians and mafia from 1992 to date[62].

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of the party system, thanks to the Mani Pulite inquiries, brought the mafia

to look for new political representatives engaging a negotiation with a part of

the institutions. The story began on January 30, 1992 when the Maxi Trial

against Cosa Nostra finally came to

an end; for the first time in the Italian history the Supreme Court confirmed

life sentences for mafia bosses. This was possible thanks to a magistrate who

fought against the Mafia, Giovanni Falcone; while working with the Minister of

Justice, Claudio Martelli, he suggested a rotation criterion to avoid the judge

Corrado Carnevale, also known as the “sentence-slayer”[63],

to preside over the Supreme Court for that trial. According to the prosecutors

of the “Trattativa” investigation the

DC didn’t respect a “pact” with Cosa Nostra that should have granted impunity

for mafia bosses. In February 1992 the Minister Calogero Mannino (DC) told the Maresciallo

of the Carabinieri Giuliano Guazzelli “At this point they’ll kill me or Salvo Lima”.

A month later mafia killers on a motorcycle murdered Salvo Lima, member of the “corrente Andreottiana”[64].

A few days later the chief of the Italian Police, Vincenzo Parisi, wrote in a

secret note “death threats have been directed towards the Prime Minister, Giulio

Andreotti, and the Ministers Vizzini and Mannino… terroristic attacks against

DC, PSI and PDS[65]

members expected in March-July. Strategy that includes massacres.”On March 20, Vincenzo

Scotti, Minister of the Interior, stated: “hiding to the citizens that we are

facing an organised crime attempt to destabilize institutions is a huge

mistake”. Andreotti, however, defined this warning a hoax.

At the

end of March 1992 Vito Ciancimino, former mayor of Palermo, met Bernardo

Provenzano, one of the Cosa Nostra fugitive

bosses. This latter told him that Totò Riina, the then boss of the Corleone

syndicate[66],

“has been guaranteed something important by someone and his intentions are not

good at all”. On April 24 Andreotti government fell and between April and May

Mannino informally met several times Vincenzo Parisi, Bruno Contrada[67],

and the chief of the Special Operations Group (ROS) of the Carabinieri, Antonio

Subranni; these meetings were probably an input to create contacts with Cosa Nostra. On May 23 the judge Giovanni

Falcone, his wife and three bodyguards were killed in the blast caused by the detonation

of half a ton of explosives placed under the motorway that links the Palermo

International Airport to the city of Palermo, the Capaci massacre. Two days

later Oscar Luigi Scalfaro was elected President of the Republic in place of

Giulio Andreotti. On May 30 the then Captain of the ROS, Giuseppe De Donno, met

on a plane Vito Ciancimino’s son, Massimo, asking him to meet informally his

father. This is when the negotiation got started.

In the

first half of June Vito Ciancimino talked with Provenzano about the ROS’ request;

the boss told him to try to be a mediator between Riina and the Carabinieri. At

the end of June the first meetings between Ciancimino and the Captain De Donno

took place. Riina, informed of the negotiation, was euphoric and started to

write the “papello”[68],

a list of requests that had to be delivered to the State. On 28th June Nicola

Mancino replaced Scotti at the Ministry of the Interior while the day after

Liliana Ferraro, who took the role of Falcone within the Ministry of Justice

after his death, told Borsellino, magistrate and co-worker with Falcone, of the

negotiation between ROS and Ciancimino. On July 1 Borsellino was in Rome to interrogate

the “pentito” Gaspare Mutolo when the

Ministry of the Interior called him to meet the new Minister, Mancino, who was

taking office. Right before meeting the Minister, Borsellino encountered Bruno Contrada

who told him a joke about Mutolo’s “pentimento”[69]

that was still secret at the time. In the evening Borsellino told his wife “I

breathed death”. During the first half of July Ciancimino received the “papello” from Riina, twelve requests

that the Carabinieri evaluated as unacceptable; the negotiation interrupted. On

July 15 Borsellino was sick, vomited[70],

came back home and talked to his wife “I’m watching the mafia live; I’ve been

told that Subranni is punciutu”. Four

days later he died in the massacre of Via D’Amelio together with five

bodyguards while he was visiting his mother’s house.

At the

end of August the negotiation restarted, the ROS changed their strategy and

wanted Ciancimino to help them in arresting Totò Riina giving him maps of the

city of Palermo. In November 1992 Ciancimino gave these maps to Provenzano and

when he had them back he noticed that Provenzano did some marks, indicating

Riina’s hiding places. On January 1993 the boss of Cosa Nostra Totò Riina was finally arrested. However the

Carabinieri Captain Sergio De Caprio[71]

didn’t’ search his hideout and when this happened it was completely emptied. Cosa Nostra members responded to the Riina’s

arrest with a series of attacks[72].

In November 1993 the new Minister of Justice, Giovanni Conso, let more than

three hundred 41-bis[73]

expire representing the first real concession of the State, threatened by the

massacres. A failed attack at the Olympic Stadium in Rome, which should have

occurred in October 1993, has been recently explained by the “pentito” Gaspare Spatuzza. He told the

magistrates that the attack should have been the final attempt in trying to

convince the State to reform the 41-bis but the bomb didn’t explode due to

technical problems. Nonetheless he was ordered not to try again because,

according to Spatuzza, two new political figures, Silvio Berlusconi and

Marcello Dell’Utri were creating a party, Forza

Italia, considered by Cosa Nostra

to be the new mediator between institutions and mafia[74]

[75]

[76].

This

story represents the prosecutors’ point of view and the “Trattativa” inquiry, started

in 2009, is still going on. Nowadays mafiosi

and politicians are under investigation including the co-founder of

Berlusconi’s party Marcello Dell’Utri.

Solutions

of such complex problem should probably regard reforms concerning all the

aspects of the civil and political Italian life. First of all mafia has to be

thaught in schools so that future citizens would be fully aware of the problem,

especially in the southern regions the culture of legality should be a priority

at all levels of education; the judicial and police sector need far more

financial resources to fight against organised crime; magistrates and policemen

have to be as professionally prepared as mafia organisations. According to

Freedom House Italy is “partly-free”[77]

for what concerns the freedom of press. Public television is in the

government’s hands while the other main channels belong to former Prime

Minister Silvio Berlusconi. This situation determines a serious problem because

the lack of a free information system prevent people to understand what certain

politicians really are and what is really going on in their country. A part

from a few television programmes only local media report mafia related news, especially

in those regions where people are already partly aware of the reality surrounding

them. The benefits coming from the Internet technology are still limited because

Italy has the worst broadband speed connection of Europe[78].

For these reasons, all the knowledge provided so far is not discussed

nationwide and politicians don’t want to improve the information system. In the

end economic reforms are fundamental, mainly because mafia is after all a huge

economic obstacle. Such reforms should include more transparency and control of

the Italian market even though they should concern also other countries since mafia

is already a multinational corporation, making business everywhere around the

world.

In

conclusion, mafia organisations are not just criminal groups but an important

and persistent aspect of Italian politics. Since 1861 they both need each other

to maintain their power sharing same values and ideas about the world and life;

they represent a system of power and mass control. This system lives within democratic

institutions that aren’t showing political will along with constant and

effective actions. Even though it looks like an enormous enemy, mafia is not

invincible and as Giovanni Falcone stated: “The Mafia is a human phenomenon and

thus, like all human phenomena, it has had a beginning and an evolution, and

will also have an end.[79]”

Bibliography

Antimafia.altervista.org

Avvisopubblico.it

Bianchi D.,

Rio R., (2013), “L' impero della 'ndrangheta. Radiografia di un'organizzazione

criminale in continua espansione”, Perrone Editore, Roma.

Buscaglia

E. and van Dijk J., (2003), “Controlling Organised Crime and Corruption in the

public sector” Forum on Crime and Society, Vol. 3.

Commissione

Parlamentare Antimafia, (1999), Dossier “Conoscere le mafie, Costruire la

legalità”.

Corriere

della sera http://www.corriere.it/cronache/09_dicembre_04/spatuzza_deposizione_bunker_mafia_da1907d4-e09c-11de-b6f9-00144f02aabc.shtml, 14/11/13

Genova web

Gounev

P., Ruggiero V., (2012), “Corruption and Organised Crime in Europe”,

Routledge.

Grasso P.,

La Volpe A., (2009, “Per non morire di mafia”, Sperling & Kupfer, Milano.

Gratteri

N. and Nicaso A., (2006), “Fratelli di sangue”, Pellegrini Editore, Cosenza.

Il Giornale

http://www.ilgiornale.it/news/calabria-colombia-d-europa-qui-coca-fattura-35-miliardi.html, 14/11/13

International

Business Times

Kerry J.,

(1998), “The New War: The Web of Crime That Threatens America's Security”,

Touchstone.

La Repubblica

http://www.repubblica.it/2008/05/sezioni/cronaca/ndrangheta-usa/ndrangheta-usa/ndrangheta-usa.html, 10/11/13

Rogari S.,

Manica G., (2011), “Mafia e politica dall’Unità d’Italia ad oggi. 150 anni di storia”, Edizioni Scientifiche

Italiane, Napoli.

Saviano R.,

(2006), “Gomorra”, Mondadori, Milano.

Saviano R.,

(2013), “Zero Zero Zero”, Feltrinelli Editore, Milano.

Servizio

Pubblico: "Vedo, Sento, Parlo". Roberto Scarpinato https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lYoikm3yO-I, 15/11/13

Sostiene

fassino: i voti della 'ndrangheta al PD http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zdfG63rcqsc,

9/11/13

Treccani http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/portella-della-ginestra-strage-di_(Dizionario-di-Storia)/, 23/11/13

Vent' anni di trattativa Stato-Mafia

(video-cronistoria del fattoquotidiano.it) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qADkCs2xd7g, 19/11/13

Verona-In

http://www.verona-in.it/2013/11/20/gratteri-verona-oggi-e-il-politico-che-chiede-aiuto-alla-mafia/,

20/11/13

[2] Rogari S., Manica G., (2011), “Mafia e politica

dall’Unità d’Italia ad oggi. 150 anni di storia”, Edizioni Scientifiche

Italiane, Napoli.

[3] Commissione Parlamentare

Antimafia, (1999), Dossier “Conoscere le mafie, Costruire la legalità”.

[4] Cosa Nostra,

Camorra, ‘Ndrangheta

[7] ‘Ndrangheta

is called “Onorata Società” by its

members.

[9] Gratteri N. and Nicaso A., (2006), “Fratelli di

sangue”, Pellegrini Editore, Cosenza.

[13] Members of the Camorra

[15]

Commissione Parlamentare Antimafia, (1999), Dossier “Conoscere

le mafie, Costruire la legalità” chapter 4.

[16] Camorra

syndicate.

[17] Saviano R., (2006), “Gomorra”, Mondadori, Milano.

[22] Members of the mafia

[23] Saviano R., (2013), “Zero Zero Zero”, Feltrinelli

Editore, Milano.

[28]

Gounev P., Ruggiero V., (2012), “Corruption and Organised

Crime in Europe”, Routledge.

[30] Members of the Mafia.

[31] Grasso P., La Volpe A., (2009, “Per non morire di

mafia”, Sperling & Kupfer, Milano.

[33] Gratteri N. and Nicaso A., (2006), “Fratelli di

sangue”, Pellegrini Editore, Cosenza.

[34] “soldiers”

[35] “Representative”

[36] “Mafia Commission”

[37] Commissione Parlamentare

Antimafia, (1999), Dossier “Conoscere le mafie, Costruire la legalità”.

[39] Members of the ‘Ndrangheta.

[40] In this case the word refers to the ‘Ndrangheta rank

[43] Direzione

Distrettuale Antimafia

[45] Saviano R., (2006), “Gomorra”, Mondadori, Milano.

[46] Bianchi D., Rio R., (2013), “L' impero della

'ndrangheta. Radiografia di un'organizzazione criminale in continua espansione”,

Giulio Perrone Editore, Roma.

[48] Buscaglia E. and van Dijk J., (2003), “Controlling

Organised Crime and Corruption in the public sector” Forum on Crime and

Society, Vol. 3.

[49] Kerry J., (1998), “The New War: The Web of Crime That

Threatens America's Security”, Touchstone.

[51] “political faction”

[52] “New Organised Camorra”

[57] "he who has repented", the word designates people in Italy

who, formerly part of criminal or terrorist organizations, following their

arrests decide to "repent" and collaborate with the judicial system

to help investigations.

[62] It’s not clear if this negotiation stopped or it’s

still going on right now

[63] Because of the

high number of mafiosi convictions overturned on appeal in his court for

technical issues

[64] “Andreotti political faction”

[65] Partito

Democratico della Sinistra (Democratic Party of the Left)

[66] Riina was still a fugitive at the time

[68] The most important request was the removal of the

41-bis

[70] Borsellino, according to his wife Agnese, considered

the Carabinieri something “sacred” and incorruptible. Comprehensively he was

really shocked by what he was told.

[72] On 14 May, 1993 a bomb exploded in Via Fauro in Rome

but caused no injuries. On May 27 a bomb burst in Via dei Georgofili in

Florence causing the death of five people including a fifty days old baby. On

July 27 another bomb killed five people in Milan.

[73] Provisions

including very restrictive measures for Mafiosi in jail, they are isolated and

are not able to communicate with the external world.

Etichette:

'ndrangheta,

alessandro,

camorra,

cosa nostra,

d'alessio,

essay,

italy,

mafia,

mafie,

sacra corona unita,

system

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)